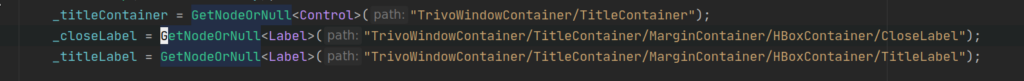

It has been quite some time since my last post. Since then lots of work has happened on Trivo in Unity. I had ported most of the old systems outside of all the old user interface code since that was mostly specific to Godot.

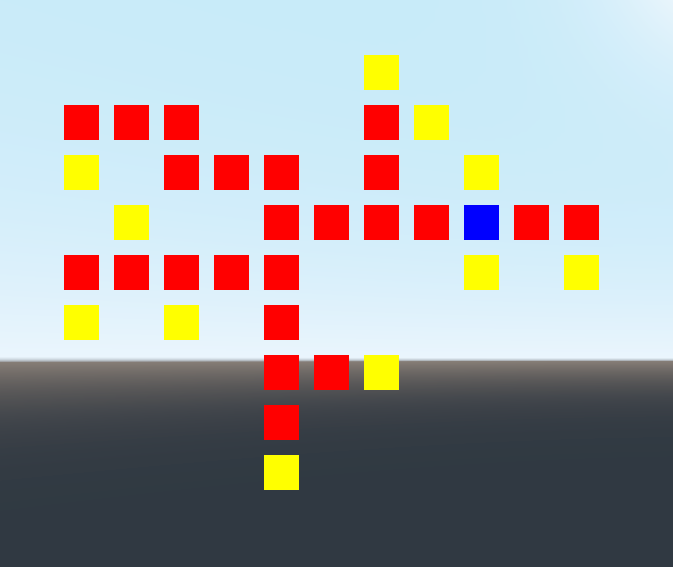

The last thing I worked on was, after getting the A.I behaviour trees working in Unity properly, was messing with Unity’s inverse kinematics with the purpose of moving the character’s palm towards a location to make it look as if they were casting a spell without a dedicated animation for it.

Here is a video below of me experimenting with that:

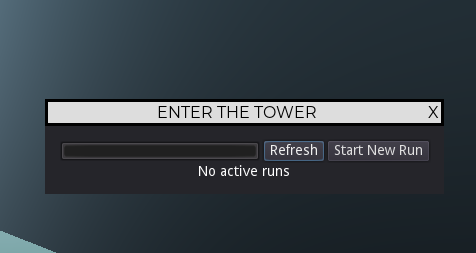

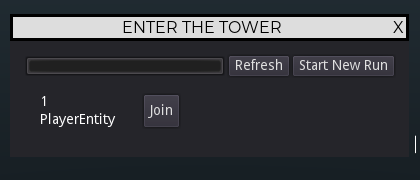

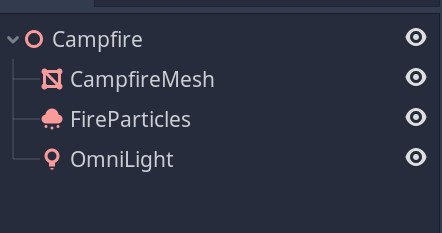

I was quite happy with the result. I also managed to get tower floors generated out of random rooms with all their doors aligned properly.

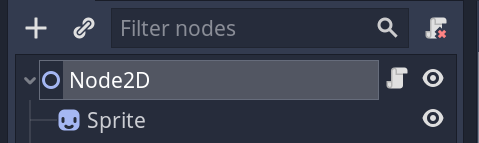

But as I continued working in Unity on this project, I felt like I was still so far from my goal and decided to take a step back and go back to Godot 3.5 and create a simpler 2D game. The idea being that I could finish a 2D game in Godot in a short amount of time before going back and continuing work on my 3D game in Unity.

I’ll be posting more about that in the future, but here’s a little spoiler: It’s a top down game where you control a ship!

Until next time!